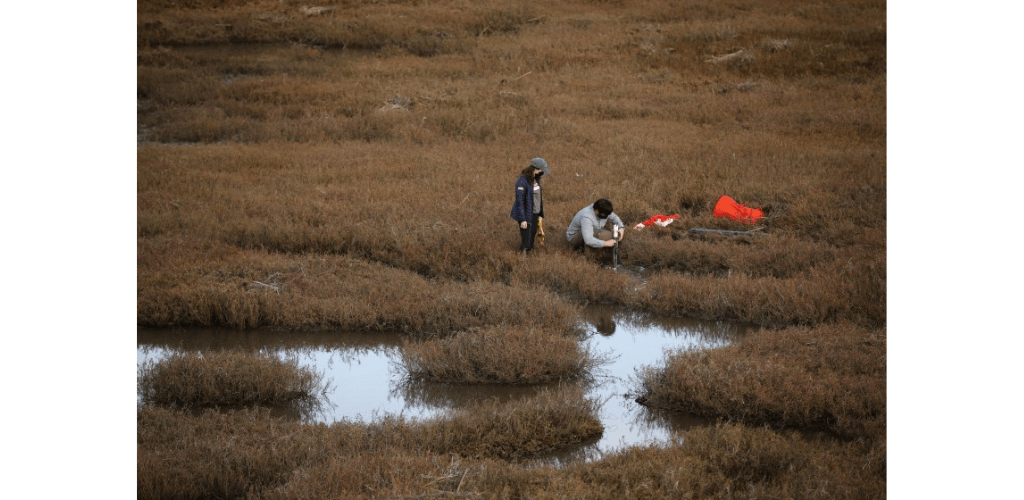

“They are the best ecosystems on the planet for taking carbon out of the atmosphere and storing it in the ground for a long time,” said Matt Costa, a postdoctoral researcher with the Center for Climate Change Impacts and Adaptation, as he took sediment samples from a corner of San Dieguito Lagoon on an overcast day earlier this month.

The salt marshes and seagrass beds that dot the San Diego County coast are some of the most biologically productive places on Earth, brimming with fish, waterfowl, crustaceans and insects. Most were destroyed during decades of development, as cities and subdivisions grew up on the coveted beachfront land.

Only about 10 percent of California’s original wetlands remain, but those that do play an outsize role in coastal environments, sheltering shorebirds, nurturing fisheries and filtering water. They can also counter the effects of climate change by buffering storm surges, and even help reduce the rate of warming by capturing carbon. Researchers refer to this process in lagoons and wetlands as “blue carbon.”

“Those that remain play a really important role for habitat, birds, fish, and they are beautiful places to visit, but they sequester and store carbon, too,” said Zack Plopper, associate director of Wildcoast. “Restoration in the past has really been focused on habitat value, and how do we preserve the biodiversity. But we can also restore these wetlands so they pull in more carbon from the atmosphere.”

The organization received a $42,000 grant from the San Diego Foundation in May to conduct the first countywide assessment of blue carbon in local wetlands. They’re visiting San Dieguito Lagoon, Kendall Frost Marsh at Mission Bay and other sites, to determine “how much carbon is there, and with sea level rise, what’s at risk,” Plopper said. Last year, they also won a $1 million, four-year grant from the state Ocean Protection Council to restore 43 acres of wetland at Batiquitos and San Elijo Lagoons, with the San Dieguito River Valley Conservancy, Batiquitos Lagoon Conservancy, and Nature Collective.

The inspiration for the study came from Wildcoast’s work restoring mangroves in Baja, Mexico, Plopper said. The organization began improving the ecosystems in order to shore up their wildlife value, then decided to measure how much carbon that habitat holds. As researchers seek ways to cut greenhouse emissions from cars and factories, they have also looked at how ecosystems can capture carbon from the atmosphere, and lock it away in soil and plants.

“Our research in Mexico showed that 19.5 million metric tons of carbon is stored within our project area in Mexico,” Plopper said. “That’s the equivalent of about 1 million people’s annual carbon emissions in the United States. And that’s just one area. So it shows on a whole, that these forests store huge amounts of carbon. We have to decarbonize, using renewable energy, and driving clean vehicles, but we also need to conserve these important ecosystems. It’s what’s called a natural climate solution.”

Along with mangroves, salt marshes and seagrasses are some of the heavy hitters in carbon sequestration. Costa said that’s likely because thick layers of wet, silty soil trap organic matter in low-oxygen conditions that leave it intact in the ground for centuries, instead of allowing it to decompose and release carbon back into the environment.

“By creating an environment that has lots of carbon but is low in oxygen, it makes it harder to break it down,” he said. “Combine that with all the plants that are taking in carbon, and that means that carbon takes a one-way trip out of the atmosphere and into sediment.”

To measure just how much of the element coastal wetlands can capture, Costa and colleagues have been visiting a section of San Dieguito Lagoon across from Del Mar Dog Beach to take samples of the sediment deposited there. It’s a particularly valuable spot because this particular patch of wetland has never been developed, so it holds an undisturbed record of soil composition over time.

Throughout the fall, the researchers conducted a transect across the site, extracting cores of sediment several feet deep at each of several visits. The area comprises two habitat types: sea grass beds dominated by cordgrass, a tall perennial; and salt marsh featuring pickleweed, a plump, salty succulent. On the final trip, fish jumped in the lagoon, while shorebirds swooped above them. A long channel carved through the middle of the site was pocked with holes made by fiddler crabs and other tiny creatures.

Treading carefully down the sandy slope and across the muddy bottom, Costa hauled a device called a “Russian peat corer,” designed to extract samples from peat bogs or other swampy environments. Costa hammered the pole into the mud, and then turned the blade around it to carve out a core of sediment 34 centimeters long, with varied textures and shades of green, brown and tan mud.

“It’s a layer cake of dirt,” he said. “It is a smelly, muddy cake.”

In the improvisational tradition of field science, he then used a kitchen spatula purchased on eBay to slice out sections, dropping them into glass jars to return to the lab. There, they’ll grind up the samples and analyze their content to determine how much carbon is trapped in the sediment, and even what kinds of vegetation grew there in decades past.

“These samples are like time capsules,” he said. “They’re sequestering carbon and putting it someplace where it won’t be disturbed for hundreds of years.”

In recent decades, coastal communities have recognized the value of lagoons and marshes for sheltering wildlife and protecting coastal communities from flooding. Restoration projects are in the works at wetlands throughout California, and researchers said they hope their study can inform those efforts, adding carbon storage to the benefits these environments can provide.

By studying them, Costa said, researchers can piece together “how to protect the most valuable spots for carbon, and in the future, hopefully, manage them to create more.”

This article was originally published in The San Diego Union-Tribune. To read the original article click here.

You must be logged in to post a comment.